Breaking Water

Rachel Litchman

I. STILL WATER

Dead wind at the shore, Lake Michigan where a pool of water waits in anticipation. The sun has just disappeared behind the horizon and the moon rises. It’s night, and the lifeguards have left their wooden perches (their look-outs) empty.

Out by the boardwalk, a cool breeze shivers, sweeps loose the grains of sand into a small vortex. Atoms intersect with the flight paths of mosquitos, a wave of earth and mist stitched together over the landscape like smoke.

Tonight, someone has chained off the dock with a No Entry sign, and a metal chair sits far off in the water.

Someone has put it there—maybe as a joke—but now the algae has come and clawed over it, and nothing is funny anymore.

Six months from now, I’ll come back to this beach to watch fireworks. I’ll sit on the sand and watch a woman cup her hands over a dog’s ears to block out the sound of a loud burst. A man will come to my school to talk about drowning. I’ll read a book where the character will say “No.”

But tonight there is no lifeguard. In a kitchen somewhere, a mother fills a pan with hot water.

In an auditorium, a man stands with a power-point slide empty, a girl types in quietly (in the safety of her room) suicide by drowning in a Google search box, a river swallows every body that touches it,

and in an ocean, the tectonic plates shift, and then drop, swallowing magma and shrieking noise.

I’ve come here tonight on my bike and left it chained to a bike rack by the train station.

I wanted to walk here by foot, down the steps, to see the water.

But when I turn around the chair is still empty, and the moon is empty. And the water is waiting, a blue sheet of paper that disappears behind a horizon.

This is before anything happens.

II. RIPPLE

One drop,

And the ache begins in my chest like a bruise rotting—

Two—like a stone falling,

And I pull the blue towel close to my body.

It’s Colorado, the summer before fifth grade, at overnight camp. In the past few months, I’ve spent my days shopping at Uncle Dan’s stores, buying swimsuits and climbing gear. I’ve decided to go to a summer camp here because something about the mountains allured me. A false sense of escape from the problems at treeline—

Where the air was thinner and the rocks higher,

It seemed the only thing that mattered was survival.

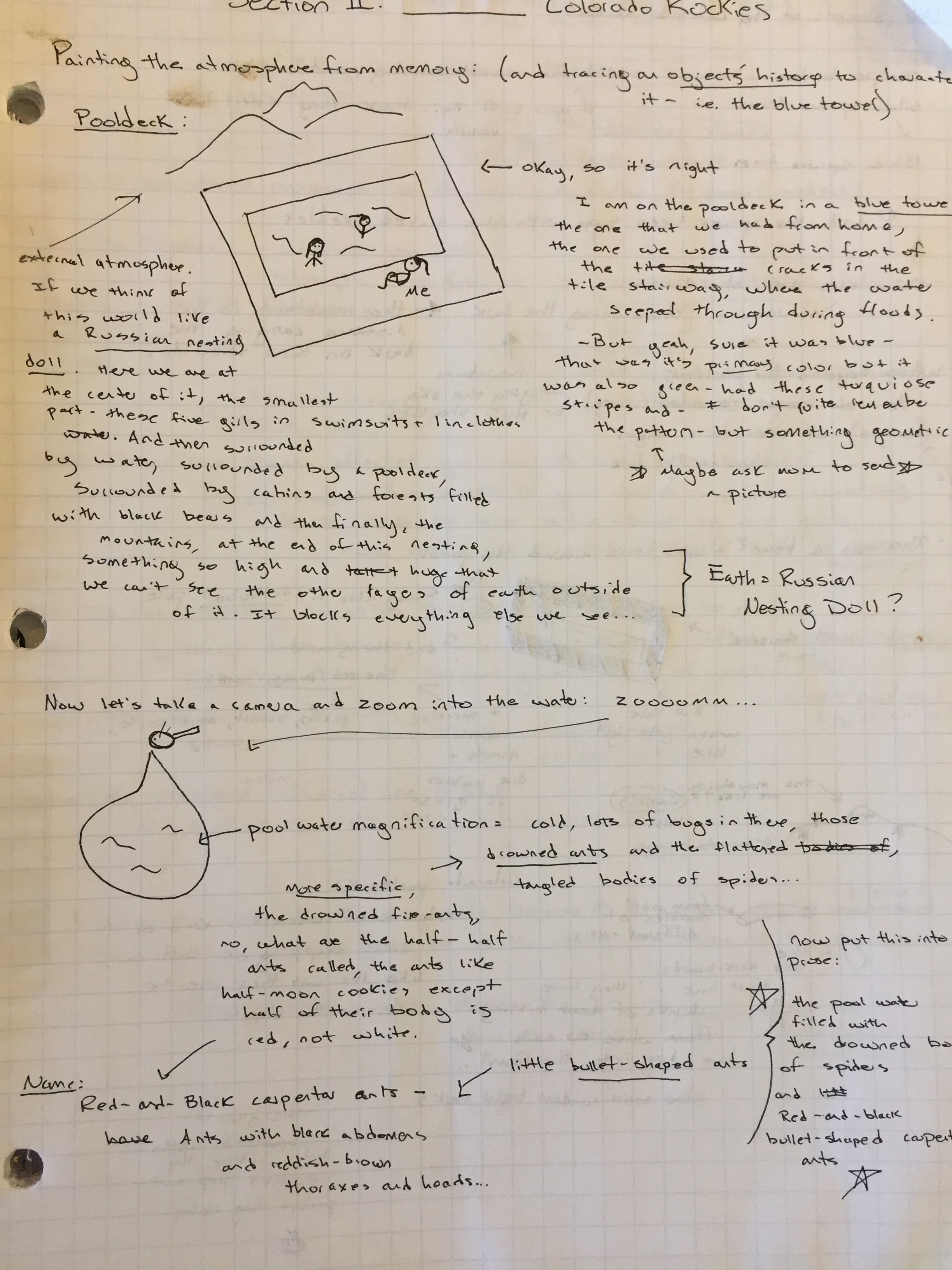

I’m on the poolside that night huddled in a blue towel. Around me, the black humps of the mountains shoulder the dark in the distance. I think of the world in that moment as something concentric, a Russian nesting doll. Here we are at the center of it, the smallest part, five girls in swimsuits surrounded by water, my body on a pool-deck surrounded by towels, the concrete of the pool-deck surrounded by cabins and forests filled with black bears and then finally, on the outskirts, enclosing the edges, the mountains.

“Get in the pool with us.” The girls in swimsuits chant this at me.

The ringleader, a girl with red hair, paddles around on a blue kickboard, chunks of foam missing from where her nails have dug into it. She flops onto her back and lets the water rush over her.

Two days ago, the girl with red hair dumped her trashcan on my bed, piles of used Band-Aids and toilet paper. A group of girls locked me outside of the cabin and barricaded the doors.

The chant gets louder. Come on. Come on. Get in the water.

The girl with red hair swims toward me.

“Rachy Bug,” she says. “Get in the pool with us.”

She rises from water.

III. SURGE

Remember: you are eleven years old and your hair is in pigtails.

Remember: your hair is in pigtails and this is why you are a target.

Remember: your sense of time is warped.

Remember: you feel a sinking feeling in your chest.

Boys will be boys and girls will be girls.

You have gotten bruises before. You should be used to this.

IV. STORM

Flashback to thunder:

When I was younger,

I used to lie in bed and hear a world rumbling. My room was in the basement where the lights in the hallway cast black shadows of books on my floor and the wind hit up against the windows, making small moaning sounds.

I was afraid of something in the dark, something silent. I used to sleep with a nightlight on, and a textbook against my chest.

Outside, the thunder reminded me of bombs falling. I would think of a war raging on my front lawn, men riding horses and soldiers on foot launching huge stones from catapults.

I’d rise, push off the covers.

When I’d press my face against the window, I’d watch the lightning outside unzip the sky.

What is inside the white space where the sky breaks open?

If I crawled through, what other world would it bring me into? Far away from this?

*

Flashback to floods:

Every night that it rains, the pool water rises. The ocean gets higher, and geckos find their way out of the rivers, onto the streets.

Tonight, I sit on the pool deck, my head pressed into my knees.

On the concrete, the red and black carpenter ants scatter like empty bullets. The girls in the pool splash water at me.

Since I left, I haven’t thought about my mother for nearly two weeks.

I write letters sometimes, say camp is going fine. I tell my mother I need a new bottle of soap. The Band-Aids have run out and I’m too afraid to go to the nurse to get some. Send toothpaste. Please, a box of crackers, a pack of gum.

Dear Mother,

The girls are nice to me. I have friends here. I’ve climbed four different mountains and it only gets easier. The feet learn to step into grooves, follow patterns.

The body learns how to fold pain into itself.

The body learns how to ripple into itself, shut out hurt by making waves.

The counselor does nothing.

The girls chant “Rachy Bug, Rachy Bug, get in the pool.”

V. LIFEGUARD

The night that it happened, the camp counselor was there. Lying on her side with her earbuds in. The moon rose and the wind rustled the aspen trees in the distance.

The girls came up to me.

One of them put her hand around my arm and pulled me out from under my towel.

“Let go of me!”

The girls laughed. I started to cry harder, and some part of me reached toward the letters I’d sent to my mother. It’s good here, it’s good here, it’s good here, I’d told her, and yet somehow, in that moment I could not convince myself of this.

The girls pried the towel off of my shoulders and they hoisted me to my feet. Two girls hopped back into the water and tugged my ankles toward them. I writhed. Their laughs rippled through me and they pushed at my back. My knees buckled.

My head struck the concrete and a wound opened.

Somewhere, far away from here, the pool water surged up through the grates in the concrete.

Ant bodies and mosquito legs oozed out through the slits.

RACHEL LITCHMAN is a high school senior at Interlochen Arts Academy. Her poetry and prose have been recognized by the Luminarts Cultural Foundation, The National Scholastic Art and Writing Awards, and The Glimmer Train Press Short Story Award for New Writers. Other work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Colorado Review, New South, The Mud Season Review, The Offbeat, and others. She is currently a poetry reader for the Adroit Journal.

A Note on Process